Bad news for UK chemistry. It looks like the subject is in trouble once more. Undergraduate chemistry courses at Aston University and the University of Hull are slated for closure and Hull’s chemistry department could close. Other departments around the country are creaking under the pressure of tightening university finances.

Why is this happening now? It’s all the result of a funding squeeze that’s affected not just chemistry departments but universities around the country. Brexit and government efforts to cut immigration have led to falling numbers of international students in recent years. These students pay far more for their courses than domestic students, so are being used to subsidise the courses of students who live in this country. The tuition fees domestic students are charged have also not changed in years, as successive governments have held them at £9250 since 2017. Added to this perfect storm is the fact that things are simply more expensive – inflation has pushed up the cost of everything from energy and water to consumables and reagents. As chemistry is one of the most expensive courses to run, university administrators are looking there first in an attempt to cut costs. Senior figures in the chemistry community are warning that the proposed closures at Hull and Aston could be the start of many more.

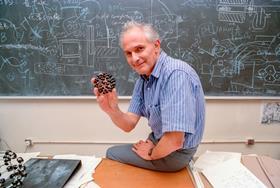

Readers may remember a similar crisis hitting chemistry in 2004. At the time, there was concern at falling numbers of students studying the subject. This was followed by the University of Exeter closing its chemistry department. Then, two years later, Sussex said that it planned to close its department to save money. What followed was an amazing mobilisation of support for UK chemistry. Emergency sessions were held at the Commons science and technology committee, early day motions submitted, scientific societies campaigned, and letters and stories made it into the national papers. The closure of Sussex’s storied department was averted in the end, thanks to a campaign spearheaded by buckyball Nobel laureate Harry Kroto. The happy coda to this era is that student numbers rose once more in chemistry and some closed departments even reopened.

The warning signs now are that chemistry is in trouble once again. In 2020, the University of Brighton withdrew its undergraduate courses and, in 2022, as part of cost saving measures, the University of Bangor closed its chemistry department with the loss of 18 staff. The number of chemistry undergraduates peaked in 2017/18 at 19,000 and has fallen by 3000 since. The number of chemistry departments, which had been rising, has also started falling again. (Chemistry World will be investigating these trends further in a health check on the state of UK chemistry at the start of October, examining the figures that explain why the subject is in trouble now.)

So, what can be done? Another high-profile chemistry hero, like Kroto, who can be the face of the campaign to save chemistry would be a great start. However, a figurehead is just that and a huge amount of work will still need to go on behind the scenes, led by scientific societies and academics. The case needs to be made to MPs and the government that chemistry provides a vital service to the country in all the jobs and industry it supports. It would be great to see government make a commitment to chemistry like that made in 2006 – there was even funding to promote the subject to students. However, in today’s climate I think this support will be less forthcoming as the government faces significant challenges on so many fronts. But there is still an opportunity here. With so much concern about a stagnating economy, chemistry is one subject that can’t be left to wither. After all, chemistry provides the skilled workers to power the high-tech, sustainable society the government ultimately wants.